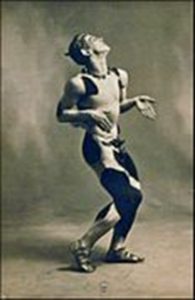

Nijinsky

Nijinsky, one of the greatest and most gifted classical dancers and choreographers of our age, was sadly one of those who was overcome by his schizophrenia and whose meteoric career was tragically cut short by this cruel condition that we now know of as schizophrenia.

Vaslav Nijinsky was born in Kiev in 1889, the son of two professional dancers; Eleonora and Thomas who originated from Poland. He was one of three children, having an older brother and a younger sister. During his childhood he had a reputation for reckless, daredevil pranks, disobedience and unusually intense levels of activity.

At the age of eight, Vaslav was enrolled by his mother at the Imperial School of Ballet in St Petersburgh (at the time the foremost ballet school in the world) where his innate skills soon got him noticed.

Nijinsky dancing with Anna Pavlova. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Vaslav graduated the Imperial School in 1907 but even before he graduated he was already dancing at the Maryinsky Theatre and before his 18th birthday he had made his professional debut even dancing with the great Anna Pavlova in Don Giovani.

Nijinsky combined great artistic presence with athletic prowess and was known for his ability for seemingly gravity-defying leaps in which he would appear to hang in the air for seconds.

After dancing for a time with the Imperial Ballet, in 1909 Nijinsky joined the Ballet Ruse, a new company formed by Russian impresario Sergei Diagelev in Paris where he danced for much of the remainder of his career. In 1912 Nijinsky made his debut as a choreographer with the Ballet Ruse with his creations of L’Apres-midi d’un Faun, Till Eulenspiegel and Le Sacre du Printemps, the latter causing fights to break out in the audience as Nijinsky’s new methods caused great controversy.

Nijinksy and his daughter Kyra taken around 1916. (Image: Unknown author, in the public domain, from Wikimedia Commons)

Nijinsky’s relationship with Diagelev, which was intimate and almost certainly sexual, continued until 1913 when Nijinsky married Romola Pulsky, a Hungarian dancer with whom he later had two daughters. He soon parted company with the Ballet Ruse but not until he had engraved a reputation as being the greatest male dancer of his time.

Later Romola would be instrumental in the creation with Nijinsky of an independent ballet company in London. However Nijinsky was already in the early stages of his schizophrenic illness by this time and Romola lacked commercial and artistic talents and consequently the project ultimately failed.

The couple moved to Romola’s native Hungary when in 1916, at the height of the First World War, Nijinsky, being an enemy alien, was interned by means of house arrest. But Diaghilev intervened to get him freed and, following support from a number of prominent people including King Alfonso of Spain and the US President Wilson, he was allowed to move to America where he continued working under Diaghilev’s leadership.

By 1917 the first signs of the mental storms that were to end his career were beginning to show through and in 1919 Nijinsky was diagnosed with the newly-described condition called schizophrenia and committed to an asylum. In the absence of any effective treatments, over the next 30 years or so he was to suffer repeated episodes of his illness and was confined on a number of occasions. He never danced professionally again.

Nijinsky in l’Après-midi dun faune.

(Image: Jean-Pierre Dalbera on Wikimedia Commons, creative commons attribution)

The early signs of his mental disturbance were not dramatic: a tendency to depressiveness, an extreme aversion to danger and a reluctance to trust even those close to him. But over time these characteristics grew in frequency and severity until they began to adversely affect his personal and professional life. His mental health began to become an issue during his performances and during one performance of L’Apres-midi d’Un Faun he refused to take his opening position on the rock and even after the raising of the curtain was seen pacing the stage fearful of starting to dance.

Those who have no experience of schizophrenia will try to see logical explanations in this kind of anomalous behaviour but for those who have endured the terrors of the deranged mind it is all too clear that Nijinsky’s behaviour in these instances belied a mind that was deeply pained and confused by the orgy of psychotic thinking that people entering their first episode of schizophrenia will inevitably experience.

During his later periods of illness Nijinsky displayed many of the disturbed behaviours so often seen in schizophrenia; recklessly jumping from windows, violence towards strangers in the street and self harming. His speech would become incoherent, described by one of his psychiatrists as a “word salad” and there would be periods of aggressive agitation followed by deep depression.

Treatments at the time, such as they were, were based on the immature knowledge that then existed about the condition: hydrotherapy, inducing physical illnesses such as fevers, and sedation with drugs were all tried with no success. In the absence of the modern antipsychotic medicines, psychiatrists at the time were casting about for treatments for schizophrenia and claims were made for a number of new therapies which we now know have little or no benefit to the patient. A number of these including psychoanalysis and insulin shock therapy were tried on Nijinsky.

Psychoanalysis by doctors who were followers of Freud and Jung, the founders of the field, was tried. Professor Alfred Adler, a follower of Freud who had developed his own brand of psychoanalysis which he called “Individual Psychology” was involved closely with his case. Nijinsky’s wife Romola also consulted the American psychoanalyst Dr Frieda Fromm-Reichman whose own theories rooted schizophrenia in poor parenting and whose view was that the blame for schizophrenia lay fairly and squarely with the mother’s parenting failures. However Fromm-Reichmann never saw Nijisnky and his treatment continued in Europe.

Looking at Nijinsky’s diaries it is easy to see why psychoanalysts were so interested in his case as his writings disclosed a mass of disparate ideas involving a range of sexual activities that psychoanalysts at the time, and often today, despite the mass of evidence to the contrary, see as the root cause of schizophrenia. However psychoanalysis did not work for Nijinsky and for that matter has never worked for people with schizophrenia despite the wild claims made by its practitioners.

In 1919 Nijinksy was also seen by Professor Eugen Bleuler, Director of the Burgholzli Institute in Zurich. Bleuler was an eminent and highly influential psychiatrist of his day and the doctor who first coined the term “schizophrenia”. Although the foremost diagnostician in his field, he was uncertain about a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The diagnostic interviews were made understandably more difficult by the language barrier: Bleuler spoke no Russian and Nijinsky no German so the conversation continued in French in which neither were particularly fluent.

Bleuler recommended that Nijinsky should be separated from his wife and suggested a Swiss sanatorium, the Bellevue, where he could rest. However the interview was followed by a further breakdown in his behaviour resulting in the police being called and Nijinsky was admitted to the Burgholzli under Dr Bleuler where he remained for a period of observation before being transferred to the Bellevue.

Later Nijinsky was given the innovative but equally ineffective insulin shock therapy devised by Dr Manfred Sakel. Insulin is a pancreatic hormone that reduces the patient’s blood sugar level. In large doses it can put the patient into insulin shock. Sakel hypothesised that this was beneficial in a number of illnesses including schizophrenia and the treatment such as it was became widely used in asylums in both the US and Europe. Nijinsky had it at his wife Romola’s request in 1938.

Sakel claimed a favourable success rate but insulin shock was always known to have a high risk of fatality and Sakel’s claims were treated with some caution by other doctors at the time. Although the practitioners claimed some success in the case of Nijinsky, it was never clear cut and the director of the sanatorium in which he was confined, Dr Ludwig Binswanger, who had always been sceptical put his foot down and the treatment was discontinued.

Today insulin shock therapy has long ago been discontinued. It was always risky and the claims of success made for it never really stood the test of time. Besides we now have antipsychotic medicines which have a proven effectiveness in treating the condition.

Nijinsky with his wife Romola taken about 1913. (Image: Unknown author in the public domain from Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the failures of these early treatment technologies Nijinsky never really lacked for care. His wife Romola was instrumental in arranging treatment by the foremost psychiatric doctors of the day. Many writers have been critical of Romola’s influence on Nijinsky seeing her as manipulative and scheming. She may well have been but nevertheless she did ensure that for several decades after his health failed he continued to receive the highest quality care available at the time.

Vaslav Nijinsky and Sergei Diaghilev in Nice.

(Image: Alexandra Botkina from Wikimedia Commons in the public domain)

Some have also said that it was childhood trauma that caused Nijinsky’s breakdown later in life and certainly he did suffer a near fatal accident at age 12 when, following a practical joke by some of his classmates at the Imperial School of Ballet, he was left with serious abdominal bleeding and was in a coma for five days. The idea that traumatic experiences during childhood can cause schizophrenia to develop later in life is not new. However this hypothesis was tested by extensive research during the latter half of the 20th century and the great weight of evidence now points to there being no link. Furthermore the epidemiological evidence is simply not there: If childhood adversity caused schizophrenia to develop later in life we would expect to see epidemics of schizophrenia following societal traumas such as the Holocaust, the Blitz or the Troubles in Northern Ireland but those epidemics have simply not materialised.

Some have also said that Nijinsky’s relationship with Sergei Diagelev the founder of the Ballet Ruse in Paris was abusive and that this caused Nijinsky’s breakdown. This would certainly seem to be a more promising candidate; however as a trigger rather than a fundamental cause.

Although the causes of schizophrenia are still not perfectly understood we now know that people who suffer from schizophrenia more often than not have a predisposition to the illness caused in most cases by genetic factors (it tends to run in families) but also sometimes by complications during pregnancy or birth. In Nijinsky’s case this must remain only speculation however his brother was confined in an asylum where he subsequently died.

But simply having the predisposing factor in no way guarantees that you will suffer from it: there is usually also a trigger – a precipitating factor – which can be stress caused by a traumatic relationship break-up which causes the predisposition to turn into a breakdown. So did the relationship with Diagelev or its breakup trigger Nijinsky’s mental illness? We can only really speculate about Nijinsky’s relationship with Diagelev in this respect. Although Nijinsky later married and had children we know that Diagelev was not the only man with whom he had intimate relationships.

While he was ill Nijinsky wrote intensively in his diary describing many aspects of his work and his personal life some of which may be accurate but some of which are clearly delusional. His diaries were kept a closely guarded secret by his wife Romola who published a heavily edited version of them later. They were then sold at auction in the1970s before being acquired by the New York Public Library.

Nijinsky continued in varying health both mentally and physically until 1950 when at age 61 he died in London of kidney disease, the official death certificate recording the cause of death as “uremia with chronic nephritis”. Romola survived him but was to die of cancer in 1978.

The final resting place of Vaslav Nijinsky in the Montmartre Cemetery, Paris, France. (Image: Takashi Images on Shutterstock)

As Peter Ostwald, Nijinsky’s biographer, tells us, the great dancer’s funeral was held in St James’ Church in Marylebone, London where extra police were drafted in to control the small crowd of 100 or so well wishers who assembled outside the Church. The pall bearers included Frederick Ashton, Serge Lifar and Anton Dolin, all giants of the dance world. His remains were laid to rest in St Marylebone Cemetery but later moved to Paris where he had spent so many productive years.

Nijinsky’s diagnosis of schizophrenia has been the subject of some discussion amongst experts since his death. He was diagnosed by Bleuler in the early days not long after the condition had been first described and since that time the criteria used to arrive at a diagnosis of schizophrenia have become much clearer and much better defined. Today where there is evidence of the symptoms of schizophrenia occurring alongside evidence of a mood disorder such as those that occur commonly in bipolar disorder, a diagnosis of schizo-affective disorder would be given and indeed this approach is taken in about a quarter of cases of psychosis. Some have argued that today Nijinsky would very probably have been given a diagnosis of schizo-affective disorder rather than schizophrenia.

Nijinsky’s story is one of the tragic loss of one of the greatest careers of the 20th century in any field. Sadly, this story is not uncommon in schizophrenia. The history of schizophrenia is littered with the stories of so many promising young careers cut short by this often cruel condition.

It was also a sad trick of history that Nijinsky was struck down before we had developed the modern antipsychotic drugs that enable so many of those diagnosed in our society today to live fulfilling lives again. His will always be a story of what may have been but let us never forget what he achieved in his all-too-short short career. As Peter Ostwald, said of him: “he was the inventor of male dancing in our time. Without him there would have been no Lifar, no Dolin, no Eglevsky, no Nureyev, no Baryshnikov: none of the magnificent men who followed in his footsteps and enriched our lives.”

Further Reading

1. Vaslav Nijinsky: A Leap into Madness, Peter Ostwald, Robson Books.

2. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press.

Author: David Bell.

Copyright © November 2017 LWS (UK) CIC.